Authored by Dr. Mary James, ND

We all know that too much stress isn’t good for our health, but we don’t always make the connection between stress and low thyroid problems or even subclinical hypothyroidism.

In fact, when women call us with thyroid concerns, we can often hear the stress in their voices. Sometimes they’ve even taken steps to boost their thyroid but still aren’t responding well — talk about a stressful situation!

You may be suffering from both adrenal stress and thyroid imbalance and not even realize it. If you’re experiencing symptoms such as fatigue, weight gain, moodiness and fuzzy thinking, seeing how underlying stress is affecting your thyroid is your first step to feeling better.

Table of contents

3 ways adrenal stress and low thyroid are connected

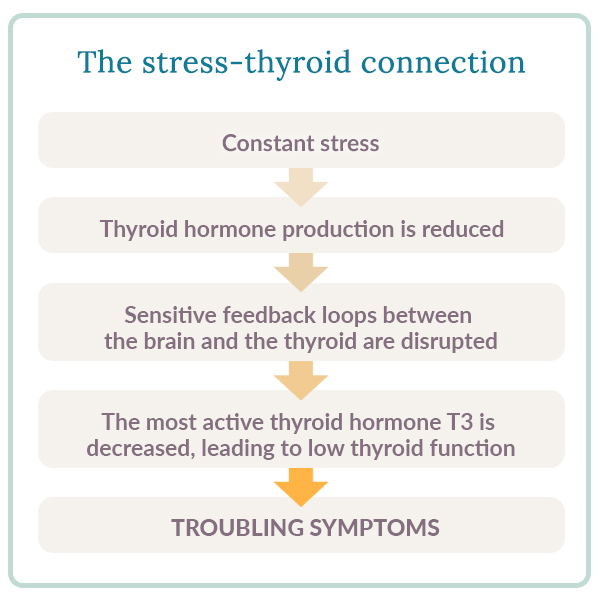

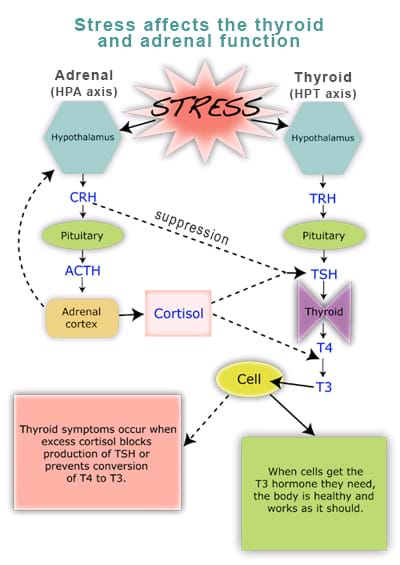

Research shows that stress-related adrenal imbalance is often connected to a low thyroid problem. Here’s why:

- The same parts of your brain control both your adrenal and thyroid hormones.

- Your adrenal and thyroid hormone “feedback loops” interact.

- Cortisol — a key adrenal hormone — and thyroid hormones work together to form your stress response.

You can see why it makes sense that when one set of hormone signals is disrupted, chances are higher that the other will be disrupted too, especially if constant stress is involved.

Thyroid symptoms caused by stress

- fatigue

- sluggishness

- cold intolerance

- weight gain

- memory loss

- poor concentration

- depression

- infertility

- hair loss

How adrenal stress can cause thyroid symptoms

You need just the right amount of cortisol for your thyroid to function optimally. Too much (from acute stress) or too little (tapped out as a result of continuous stress over time) can lead to problems. These include either overactive or underactive adrenal glands, as well as an underactive thyroid, or subclinical hypothyroidism.

How do you know what’s going on in your body?

Figuring out if you have a combination of adrenal and thyroid imbalance can be tricky. We tell women that the best way to confirm it is to compare their own experience with the symptoms listed above. (Take our Hormonal Imbalance Quiz to find out more).

Our conversations often start because women’s doctors have told them their thyroid levels are “normal” (or their TSH is “just a little on the high side”), yet something still doesn’t feel right. These women usually haven’t been given any options to support their thyroid, nor discussed the role of stress and the adrenals with their physicians.

Other women may be diagnosed by a practitioner for a thyroid disorder and be caught completely by surprise. That’s because thyroid imbalances can go on behind the scenes for months — or even years — without producing obvious symptoms.

If women have been experiencing chronic stress over time, the resulting adrenal imbalance, whether initially overactive or eventually underactive, has also been inhibiting their thyroid function.

Tips for reducing your symptoms

Try herbs that support both adrenal and thyroid function. Herbs like ashwagandha, bacopa and coleus can all relieve symptoms while supporting thyroid hormone production. Other herbs have powerful effects on adrenal function and help reduce the negative side effects of underlying stress, such as astragalus root, Siberian ginseng and cordyceps.

Get enough of the right vitamins and minerals

Selenium and iodine are the most essential minerals for producing thyroid hormones and ensuring that your thyroid works the way it should. Vitamins A, B, C and E also play important roles.

Eat to support healthy adrenal and thyroid function

Eating regular meals, especially breakfast, including high-quality protein with each meal and snack, avoiding sugar, and moderating caffeine intake can make you much more resilient to stress. (For more ideas, see our articles on eating to support your thyroid and eating to support your adrenals — you’ll notice a lot of overlap between the two!)

Sleep

The body’s ideal time to sleep is between the hours of 10 PM and 6 AM. Allow yourself adequate time to unwind before bed. Setting aside quiet periods during the day makes it a lot easier to relax at night. The downtime will also give your adrenals a needed rest.

Other good ideas

From five minutes of deep breathing to a peaceful walk, you always have options; there are many choices for stress relief. For instance, writing out your feelings, silencing your phone and meditation or prayer.

What about exercise? Exercise is essential for health, but exercising to the point of exhaustion can put your adrenal glands back into stress mode and elevate cortisol levels. By all means exercise, but take it easy, especially at first.

If you’re struggling to overcome symptoms, you do have options to support your thyroid and adrenals naturally. Remember that even small changes, especially if you stick to them, can add up to a dramatic difference in how you feel.

References and further reading

Mayo Clinic Staff. 2009. Graves’ disease. Definition. URL: https://www.mayoclinic.com/health/graves-disease/DS00181 (accessed 06.01.2011).

Mizokama, T., et al. 2004. Stress and thyroid autoimmunity. Thyroid, 14 (12), 1047–1055. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15650357 (accessed 05.25.2011).

Ranabir, S., & Reetu, K. 2011. Stress and hormones. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab., 15 (1), 18–22. URL: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3079864/?tool=pubmed (accessed 05.25.2011).

“Thyroid function is usually down-regulated during stressful conditions. T3 and T4 levels decrease with stress. Stress inhibits the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) secretion through the action of glucocorticoids on the central nervous system.” [Helmreich et al. 2005.]

Helmreich, D., et al. 2005. Relation between the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis during repeated stress. Neuroendocrinology, 81, 183–92. URL (abstract): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16020927 (accessed 05.25.2011).

Pizzorno, L., & Ferril, W. 2005. Chapter 32. Clinical approaches to hormonal and neuroendocrine imbalances. Thyroid. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, ed. D. Jones & S. Quinn, 647. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.

Liska, D., and S. Quinn, eds. 2004. Clinical Nutrition, A Functional Approach, 184. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine.