After a 7.0-magnitude earthquake devastated Haiti in 2010, Dr. Pier Boutin responded to the urgent call for French-speaking orthopedic surgeons. She led the first surgical team to land in Port-au-Prince, where the unimaginable suffering in the gruesome aftermath of the earthquake left a lasting impression.

Haunted by memories of all she had witnessed, Dr. Boutin traveled to Morocco to hike the Atlas Mountains in hopes of finding peace and clarity. It was there that she met a 3-year-old Moroccan boy, “Little Mo”, whose untreated clubfeet and enchanting smile captured Dr. Boutin’s heart — and compelled her into selfless action for a second time.

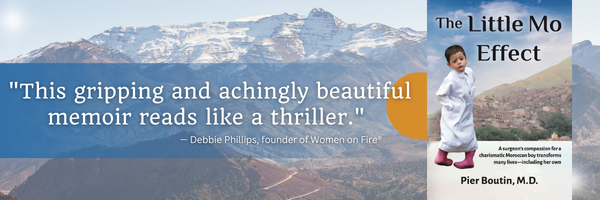

Hayley McKinnon had the privilege of interviewing Dr. Boutin about her best-selling new book, The Little Mo Effect, which chronicles the surprising and heartwarming journey that unfolded between her and Little Mo, and how her determination to help him walk again transformed both of their lives. With enchanting characters that leap off the page and brilliant observations of the humanity that connects us all, The Little Mo Effect will capture your heart, shift your perspective and inspire you to find your own purpose and joy.

Dr. Pier Boutin is a board-certified orthopedic surgeon who specializes in orthopedic surgery, osteoporosis, and the role of hormonal balance in overall health — in addition to her role as a member of the Women’s Health Network Board of Medical Advisors.

Hayley: It seems like no matter what was happening in your life, you always chose to do the right thing — even though it was often more challenging. You led the first surgical team into Haiti after the 2010 earthquake. You opened your home to a little Moroccan boy and completely transformed his life. In both of those scenarios, the solution was completely clear to you, “Just do the right thing”. Where do you think that comes from?

Dr. Pier Boutin: I think that most of us medical professionals who choose to go into this field do it because we want to help. Maybe that’s innate, maybe that’s why their personality fits that kind of work. So I think it was ingrained in me from the start. Over time, it became more and more apparent to me that I thrived when I witnessed a patient get better and heal. Especially in my field of orthopedic surgery, it’s incredibly rewarding because if somebody breaks a bone, we can perform surgery that actually brings them back to their baseline prior to injury — and they walk normally again.

That situation is very different from other fields. If you look at general medicine, if a patient becomes diabetic, the doctor will give them medication. If the patient then becomes hypertensive, they’ll get a different medication. But the patient is never returning to their baseline health. So I think that orthopedics is so fun; it’s so positive and so rewarding compared to a lot of other fields in medicine. And that direct positive feedback leads you to want more. So is it really altruism? It’s rewarding both ways. I still love going to work and meeting with my patients and being involved in their lives, in their health and in their recovery.

There’s only two body parts systems that actually go back to their original form when they’re injured. One of them is bone; when you break a bone, the injury heals with bone. The second system is the liver; when you cut the liver, it regenerates into liver new tissue, because the body can reproduce bone and liver cells. So the liver and bones are the two organs or bodily systems that actually go back to their natural form and heal with their own tissue. For instance, if you cut your skin, you heal with scar tissue — that scar tissue is not skin.

Hayley: Speaking of injury and renewal…one of the themes in The Little Mo Effect is the role of emotional pain and physical symptoms. Little Mo’s physical condition was very obvious to anyone who met him. But you were also suffering from pretty tremendous physical pain and arthritis that forced you to give up surgery for a time and really reduced your self-esteem and confidence.

But as your journey with Little Mo developed, and you began to recover your purpose, your symptoms started to fade. How much did your mental and psychological suffering impact your physical health? And do you think emotional health is always a part of the patient’s story? And if so, should we always treat it that way?

Dr. Pier Boutin: I think that stress and psychosocial issues may exacerbate symptoms. But it’s important that you don’t undermine the actual physical problem by saying, “This is just stress,” because then you’re minimizing the patient’s physical symptoms and their experience. I don’t think we can say, “Stress will actually cause the autoimmune disease,” or cause the broken bone. Sometimes, the added mental stress blinds you, and you may no longer see your way out of a situation, injury or medical condition. So I believe that it’s important to address the underlying psychosocial issues without minimizing the physical symptoms.

When I see a patient, I like to sit down and talk about their physical condition, but also about what’s going on in their life. Honestly, I think that’s the difference between a good doctor and a great doctor: somebody that can be sensitive to the impact of the psychosocial aspect on the patient’s physical health. You can’t always treat the psychosocial issues, because often patients can’t change the situation that’s causing their emotional suffering. But as a doctor, you have to hear that and you have to see how it affects the patient, and acknowledge it while you treat them. You have to help them with what you can do for their physical symptoms, to support them in whatever way you can, so they can be successful in the rest of their lives.

I’m a musculoskeletal specialist, I’m not a psychiatrist, so it’s also important to know when to refer your patients to someone who can help them with the other factors impacting their health. But even in my role as an orthopedic surgeon, I always take the time to listen and understand the patient’s mental and emotional issues and the way they influence physical symptoms. You can’t treat one without the other.

Did you know that most countries with socialized medicine have a majority of female physicians? Women are more inclined to pay attention and really listen to their patients in order to understand the patient’s life and symptoms. It’s really about service, answering the call, and taking action.

Hayley: You were the first female surgeon in the state of Florida to graduate in orthopedic surgery. How did you protect your confidence without losing the sensitive and vulnerable side that makes you such a brilliant doctor and sensitive to your patients’ needs?

Dr. Pier Boutin: I was the only woman in my field; I was 1 of 10 doctors in my residency program. The other nine people were men. I was challenged and questioned every single day because I was a woman, so I felt like I always had to show a strong, confident front. It did destroy me a little bit, little by little on the inside — but I didn’t show it. My colleagues expected strength from me. I couldn’t be vulnerable. Plus, do you really want your surgeon, who’s going to be operating on you, to show vulnerability? It’s a very fine line to walk.

Hayley: I’m amazed that you stuck with it, especially when your Chief Resident said to you, “You’re the best resident I’ve ever had — you never asked me a question!”

Dr. Pier Boutin: When I met my Chief Resident, he shook my hand and said, “You’re gonna be gone in 6 months. Because you have no place here.” Incredible. He was supposed to be training me, and I was supposed to be learning from him and asking him questions. But I didn’t ask him a single question for the first 6 months. I figured it out; I pulled the text books out, and I figured it out. It would have been nice to have some support and guidance during those times. Did it make me stronger? I don’t know.

There was a resident two years ahead of me in my program who ended up becoming a hand surgeon. He was the one who told me, “Just always do the right thing.” He knew me, and he trusted I would do the right thing. But when he put it like that, when I was in Residency, that really brought it home. I knew that was how I wanted to live my life: don’t do the easy thing, do the right thing. It might take a little bit more work, it might be a little more painful, but just do the right thing so that you can go to bed and be able to sleep at night. It’s just made a huge difference in my life. Don’t avoid something because it’s too hard. Or because you’re scared. Do it anyway. Do the right thing. Don’t ever let fear guide you.

Hayley: I think a lot of women will recognize themselves in the woman you describe when you were going to Morocco that first time. I recognized my own depression in some of the ways that you described yourself, and how you just felt like you had lost your power. And although most of the book is about how you reclaimed that power, and reclaimed your light, and sort of got back to life, were there any specific tools or practices that you would recommend for other women reading this interview, who feel the same urge to reclaim their life?

Dr. Pier Boutin: It was percolating in my head that I wanted to make a change in my life, but I didn’t see my way out of it for a long time. I think these events — the Haiti mission, Little Mo and his family — fell into my lap because I was ready for them, and I was ready to take action. When the call came for, “French-speaking orthopedic surgeons,” after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, I felt like they were literally calling my name. I had the skills. I spoke French. I was available, and I could do it. It probably sounds overwhelming, but I was ready to make that step. I think taking that first step is the hardest thing. Once I was in Haiti, I found purpose. Again, I was helping people — I was operating regularly, I was making a difference. And that’s addicting. I decided then and there that I don’t ever want to live my life without purpose. I didn’t know at that point how I was going to make it happen, but I knew that was my goal.

Suddenly, everything started falling into place, and more and more opportunities came my way. I suspect those opportunities were there before, but I didn’t recognize them because I wasn’t ready for them yet. Along the way, my girlfriends definitely knew that I needed to make a change. They’re the ones that said to me, “You need a trip, you need to change your focus,” and that’s how we ended up in Morocco, and then the Atlas Mountains. So I listened, and I took that first step. When I first saw Little Mo, I recognized immediately what this little boy’s problem was, and how I could help. That gave me purpose, and as I worked toward that goal I became stronger and more driven.

The people around you and the little suggestions of a higher path are always around you if you’re ready to hear them. A few years earlier, a woman I greatly admired had looked me right in the eye and said, “So, Pier…what are your goals?” I answered something generic. But in my head, at that time, I had no goals. I had no purpose.

Shortly after that, the earthquake hit Haiti — and I answered that call.

I understand when people feel stuck, especially in depression or darkness, and you can’t see a way out. So you can’t force it. But if someone is starting to think about choosing a different path, that first step is what makes all the difference. And some of the steps you take might not work perfectly, or you might take a few steps back. But just keep going. Like I said before, don’t let fear stop you from taking that step. Don’t let fear guide the rest of your life. How do you want to lead your own life?

When I came back from Haiti, I reached out to my friends more often, and my support system grew and gave me a lot of strength. That made a huge difference. One of the things that I had done when I was in that dark space is I pulled myself away from my friends, I kind of isolated myself. I don’t have a magic formula. I suppose the first thing would be to reach out to your friends. Make a plan; even if you’re not ready to make it, just start thinking about it. And when you see an opportunity, take it.

Hayley: Speaking of community…as I got to the end of the book, all I could think about was, “I want to help. I can’t necessarily go to Morocco, but I need to be involved.” Is there any opportunity for people who feel motivated to help the people of the Aremd Village as you were? Besides buying the book, of course. Is Soumyasjourney.com the best place to start?

Dr. Pier Boutin: All of my proceeds from sales of The Little Mo Effect are going directly to the foundation run by my daughter, Soumya, who is developing a comprehensive plan to build a school in her village in the Atlas Mountains. I adopted Soumya, Little Mo’s older sister. She’s now 17. There are seven little villages in this area, but there are no schools for girls after sixth grade near her village. Boys are allowed to leave their hometowns to go to school, but girls are not allowed to travel from home for school. Right now, girls in Soumya’s village usually quit school between fourth and sixth grade. So Soumya wants to build a school in the village for girls to learn life skills so that they can finish high school and have choices. They can get married and have children if they choose, but they deserve the opportunity to choose what they want their future to look like. They need life skills to either continue in school, or get a job and have a sense of purpose — and income.

I went back to Morocco and taught one of Little Mo’s classes. The teacher pulled me aside and said, “Mohamed is very smart. But his sister Soumya is not smart.” I stayed in touch with Little Mo’s family and when Soumya was 11 years old, they told me they were going to start looking for a husband for her. I suggested she come to school in the United States instead. So she did — and from day one, she has been at the top of the class. Her average grade is an A, and she’s presently enrolled at one of the hardest boarding schools in the country.

It just goes to show you that just one statement from a teacher or person in a position of authority can annihilate the voices — very intelligent voices — of 50% of the world’s population. It’s not that Soumya wasn’t smart enough for school, it’s that she wasn’t given the opportunity to show how smart she was. So building a school in that town is the first step to getting those young girls the opportunity to be educated, and the opportunity for the world to hear those voices that have been completely canceled.

For people who want to get involved, the best thing to do is visit Soumyasjourney.com and support her foundation — whether it be through donations, grant writing, media support, or developing the curriculum for the school itself. There are a lot of opportunities to get involved.

This value on education and empowering women has already influenced the people in her village. Soumya’s biological parents now understand how important school is. Little Mo is planning to go to college, which is almost unheard of. Soumya’s younger sister is going to continue through school.

Hayley: That ripple effect that you talk about, that just one person’s life can really spread. I mean, you’re seeing it just within one generation.

Dr. Pier Boutin: Absolutely. It’s really exciting. It’s been such a rewarding journey.

Hayley: I can see it in your eyes when you talk about the way that Little Mo and Soumya have transformed your life just as much as you changed the entire trajectory of their lives. So where’s Little Mo today? Do you get to see him very often?

Dr. Pier Boutin: I haven’t been able to see him recently because of the pandemic and our prior administration, but he’s going to come for a visit this summer. He’s doing really well; he’s top of his class in school, and school is really important to him. He’s also the goalie on the soccer team. This is the boy that couldn’t walk. He loved soccer, and playing soccer is the major pastime over there. But when I met him, he could never play with the other kids — he could only ever watch. So it’s a really beautiful, full-circle moment.

Hayley: That is incredible. So will there be more books?

Dr. Pier Boutin: My next book will be more medical. It’s an in-depth look at building bone and maintaining strong bones through every stage of life, using patient stories to show how important it is to focus on bone health beginning as early as your 20’s, and the way certain lifestyle and dietary choices impact bone-building.

My daughter Soumya is planning to write a book of her own, and her book is going to pick up where mine left off, to continue the story from her perspective. Soumya loved The Little Mo Effect because she lived it, but she was in Morocco. She wasn’t here in the US with Little Mo and me, and at that point we couldn’t communicate what was happening in English. So she had only one viewpoint. It was really exciting for her to get both sides of the story in such detail, and put it all together.

Hayley: It’s incredible to think about how many lives have been changed by your chance encounter with Little Mo and simply deciding to, as you say, “Do the right thing.” It seems like the stars aligned and then all of the pieces fell into place; from doctors to donors to hospital coordinators, the right people appeared at the right time to support you and Little Mo on your journey.

Dr. Pier Boutin: I don’t think they came out of nowhere. By that time, I’d already made a plan; in my mind, I knew I wanted to change things and find purpose in my life again. So I think that I was open to recognizing and receiving that motivation and purpose when it appeared. If you are open to it and you create space for it, it will come.

The Little Mo Effect is available on Amazon. Proceeds from the book will be donated to Soumya’s Journey, a foundation devoted to educating and empowering girls in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

Learn more about Dr. Pier Boutin: https://www.pierboutinmd.com/

Learn more about Soumya’s Journey: https://soumyasjourney.org/